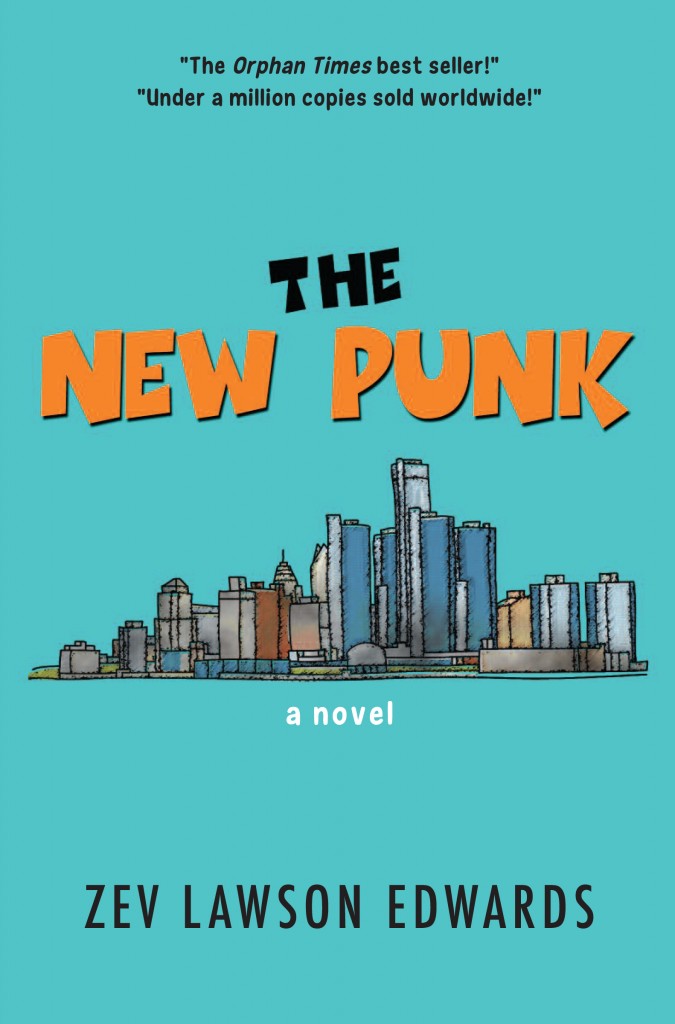

1. Desolation Row

An orphanage can be many things, but it is most like an attic where all the leftover, unwanted possessions of a person’s life go to take up space and disappear. It exists solely because some belongings are too precious and sentimental to be taken out with the trash. In that regard, all orphanages stand as a testament to the fact that some things in life are more easily forgotten than remembered.

Such a place existed in the heart of America’s most neglected metropolis, the city of Detroit. By fate, destiny, irony, or some poet’s ill-timed sense of humor, it came to be that the all-boys orphanage on 2959 Douglas Street, Detroit, Michigan—a one-time Historical Center, Social Services Office, Public Library, Performing Arts Theater, School, Fire Department—was rightly named Desolation Row, though referred to as simply “the Row” by the many orphans who took up residence there.

The orphans, like the orphanage itself, were relics of lives never lived. They came from all walks of life, representing the many different fabrics of America’s quilt. Equally unwanted, neglected, and alone, they shared a common identity and background. Born at a disadvantage, lacking in opportunity and birthright, their lives were spent looking up and asking why, while the rest of the world looked down and asked why not.

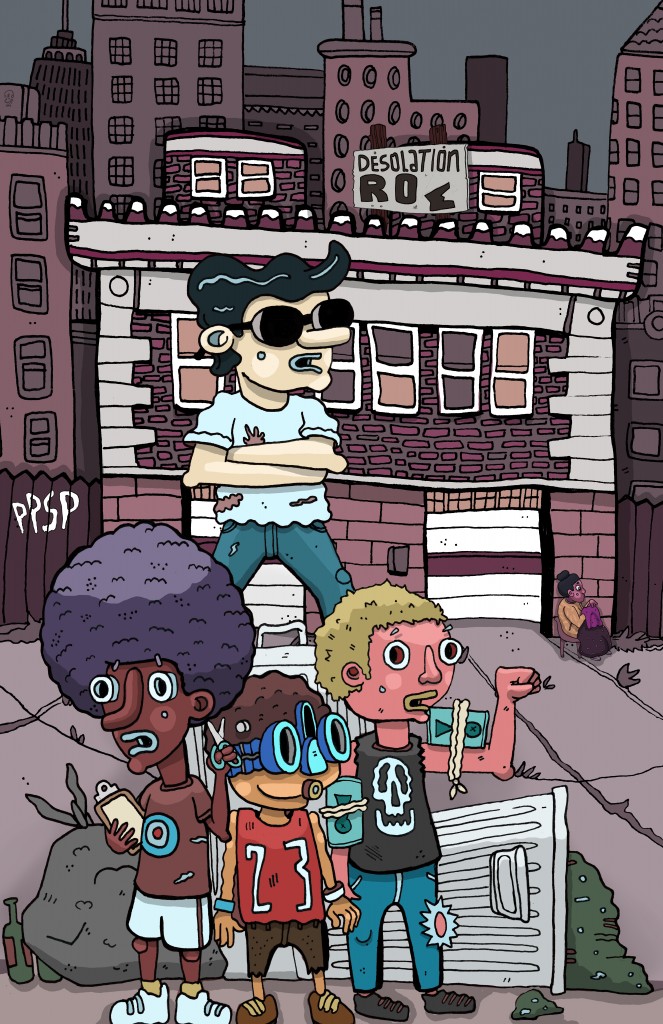

“Look sharp, men,” T.W. said, the Row’s oldest and most recalcitrant orphan. “I want roll call in 1300 hours. We have twoharlies en route as we speak. Scissors, I’ll need a status report. Ray Charles, I want a coffee, on the double, with a splash of milk. Heavy on the sugar. I repeat heavy on the sugar.”

“Roger that, sir,” Ray Charles said, a small lad of eight, weighing no more than fifty pounds soaking wet. He left T.W.’s office, the command center of the orphanage, with such haste that he forgot to close the door.

“The door, Ray Charles, the door,” T.W. called after him.

“Oh, right, sorry, sir!” Ray Charles said, putting an added emphasis on the “sir.” All of the orphans addressed T.W. as sir though they had never been asked to.

With the door closed, T.W. was able to resume pacing the space of carpet between his desk and the chair that contained his second-in-command, Scissors, age twelve. Scissors held a number of titles, such as editor-in-chief of the Row’s monthly publication The Orphan, treasurer of all financial assets related to The Cause, secretary of T.W.’s War Council, barber in charge of all haircuts at the Row, and gardener responsible for the well-kept lion-, elephant-, and turtle-shaped hedges displayed out in front of the Row.

With a pair of scissors in his hands, he was an artist—a real Michelangelo—like his idol, the fictional Edward Scissorhands. His own Afro was kept so petite and perfectly round that his head resembled a black bowling ball. Whenever orphans needed a new trim they came to Scissors, who fashioned their hair in the latest—and sometimes not so latest—trends. His proclivity for experimentation was the reason why some of the orphans had their hair styled in chic fashions popular in the distant lands of Paris or L.A., but not so much in Detroit. He was the orphan most likely to grace the cover of Vogue Magazine.

“Now, where was I?” T.W. mused to himself, continuing to walk holes in the carpet of his spacious office. Both sides of its walls were lined with bookshelves containing everything written by Hemingway, Shakespeare, Steinbeck, Dickens, Marx, Nietzsche, Rimbaud, T.S. Elliot, and many others. Believing that there was no greater or more loyal friend than a book, T.W. took to books like a cow took to grass. He stopped in front of one of the shelves, pulled a book at random, and thumbed through its pages.

“‘There is nothing to writing,’” T.W. read. “‘All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.’”

“What’s that, sir?” Scissors asked.

“Oh, nothing, just something Hemingway said.”

T.W. returned the book to the shelf and took a seat behind his giant mahogany desk. On one end of the desk sat a large globe of the Earth, while on the other was a black Remington Standard typewriter, one of the first items scavenged from the massive dump behind the Row, which then had been repaired by The Wiz, the Row’s chief technician and scientist. On the wall directly behind T.W.’s chair hung a rather large framed portrait of Che Guevara. It had a quote inscribed on the bottom:

“The Revolution is not an apple that falls when it is ripe. You have to make it fall.”

For T.W., those were words to live and die by. As a self-proclaimed anarchist, he was the orphan most likely to start a revolution, overthrow the government, and organize a new regime. He was the illegitimate child of anarchy, the devil of Douglas Street, the master of alchemy, the fire of discontent, the ambassador of hip, the messiah of punk, and only thirteen years old.

By age and appearances alone he was not a very imposing figure. His hair was as black as a starless night, slicked back in the style of James Dean, the ultimate representation of rebellion. A lone cigarette sat wedged behind his left ear. His eyes were the green of a stop-and-go sign, but since they were always hidden behind dark black sunglasses, no orphan had ever peered into them. The sunglasses never left his face, even when he slept and showered.

His face had the confidence of a rock star who didn’t want to be bothered and couldn’t care less about being understood. His attire was of a time long before his—black motorcycle boots, tight blue jeans folded up at the bottom like he was expecting a flood, a white T-shirt topped with a black leather jacket. His stature was short, but the way he carried himself made him appear taller.

T.W. leaned back in his chair, put his feet up on the desk, and retrieved a switchblade from his side jacket pocket. He clicked it open, revealing not a knife, but a comb, which he ran through his hair once, twice, three times then folded it shut and returned it to his pocket. He started to say something, but then paused and took the cigarette from behind his ear and brought it to his mouth. Scissors was quick to stand up and light it for him.

“This is the second onslaught of Charlies this week.” T.W. took a lazy drag from his cigarette. “The economy is in the slumps, so where are all of these darn Charlies coming from?”

“I don’t know, sir.”

The term “Charlie” referred to a potential adoptive parent. T.W. had heard the word on the Vietnam-era TV drama Mashed, which chronicled the life of an outcast sous-chef who worked day and night in the canteen peeling taters, while his comrades fought the tenacious Vietcong, nicknamed Charlie. Lasting sixteen seasons and starring Tom Travolta, the king of straight-to-video B-movies, it was a culinary classic.

When the economy was good, Charlies appeared like worms after a good rain. When the economy was in the dumps, like it was now, Charlies stayed well hidden underground. These particular Charlies were sprung out of the blue, like a furtive thunderstorm sneaking up on a sunny day, giving T.W. little time to prepare.

“Give me the status report, Scissors. I want an ETA, and keep it light on the details and heavy on the PIRC.”

“Sir, the Charlies in question are set to arrive at exactly 1400 hours. Big Mama started cleaning at 0700 hours. Rec room, bathrooms, dining room, and kitchen are all checked and ready. Current location the common room. Coffee and donuts delivered at 0900 hours. Donuts number a dozen, minus one.”

“Minus one? How’s that even possible?”

“Um . . . Seafood, sir.”

“Figures. After Ray Charles comes back with my coffee have him keep his binoculars on Seafood. We can’t afford anymore missing donuts. Make it a TP1.”

“Sir, yes, sir. A Top Priority Numero Uno, no problem, sir!”

“On second thought, as a precautionary measure have Chopsticks make Seafood a snack. That should keep him occupied and out of the SMRC.”

“Sir, yes, sir. Sensitive Material Related to Charlie, no problem, sir!”

Scissors was made T.W.’s number two for the simple reason he could keep track of all of T.W.’s acronyms and recite them without hesitation at any given minute. T.W. had long lost track of the meaning behind some of the acronyms he had created to make giving orders more efficient and less verbose, which was why he had Scissors.

“If he asks any questions, just tell him it’s for The Cause.”

“Yes, sir.”

The exact details of The Cause were classified Level 11—10 being the highest and 0 being the lowest. According to Spinal Tap terms, this meant that any pertinent information relating to the cause was NTKB—Need To Know Basis—and the only person who needed to know was T.W.

T.W. was about to give another order when Ray Charles, his designated runner, gopher, messenger, secretary, and do-it-all-for-nothing, came rushing into the room, nearly tripping over his own steps and spilling coffee all over the place. A loose candy cigarette hung from his mouth.

“Jeez Louise, Ray Charles, walk much?”

“Why, yes, sir. I try to walk every day.”

“I didn’t expect an answer, Ray Charles. I was being sarcastic. When’s the last time you cleaned the binoculars on your head?”

Ray Charles scratched his head and then looked up at the ceiling pensively, as if the act could bring about a recollection. Strapped to his scrawny head and covering his eyes was a pair of black binoculars, sticking out a good four inches from his face, giving him the appearance of a Navy SEAL wearing night vision goggles. The binoculars helped with long distances, but they compromised his peripheral vision, which was why he was always walking into doors, stumbling on stairs, and causing enough accidents to be classified as a first-class klutz.

His only vice was candy cigarettes, which he consumed faster than Popeye went through spinach.t the rate he was going, Ray Charles was sure to be a diabetic by the time he was old enough to smoke the real ones. Always finding himself in asinine situations, he was the orphan most likely to go the way of the lemmings and fall off a cliff.

“Ray Charles, before you trip and hurt yourself go find Muscles immediately and have him clean those goggles on your head. Make it a TP1.”

“Yes, sir. Will there be anything else, sir?”

“When you’re finished seek out Seafood and tell him to report to Chopsticks. If he gives you any lip, tell him it’s for The Cause.”

“Yes, sir. Anything else?”

T.W. took a sip from his coffee, grimaced at its strength, and waved Ray Charles away, but due to the binoculars on his head Ray Charles was unable to see the gesture and as a result stood stalwart, awaiting further orders. T.W. likewise waited for him to leave. After a brief, silent standoff T.W. ended it by saying “off with you then.”

Ray Charles saluted before heading for the door, nearly running into the wall on his way out. He at least had the good sense to remember to close the door this time.

Finished with Ray Charles, T.W. turned to Scissors. “Commence with your report, Scissors.”

“Yes, sir. Big Mama is estimated to be finished cleaning at approximately 1200 hours, give or take a window of fifteen minutes. Children under ten have been debriefed and suited up for contact. Children over ten are in wardrobe and makeup. They are currently being debriefed by Muscles.”

“Muscles, you say?”

“Yes, sir. They are in the rec room as we speak.”

“Very good. Do we have any viable Intel on the Charlies?”

“Yes, sir. The Wiz compiled a brief bio.”

“Let’s hear it.”

“The Coopers—Mary and Peter—age twenty-eight and thirty. Residence, Royal Oak. Occupations—her, a preschool teacher and him, an orthodontist. Both originally from Illinois. Married for five years. No children.”

“Hmm, Royal Oak, you say? The suburbs. Sounds like they have money. Most likely they’re unable to have children of their own, have been trying unsuccessfully for the past few years, and finally decided to adopt. They’re too young to be desperate, but we can’t chance it. Call a Code Yellow.”

“Roger that, sir.”

When it came to Charlies, T.W. had organized a five-color-coded chart to represent the likelihood of possible adoption. It started with white, moved to green, then yellow before ending with orange and red. In cases of an emergency so dire and severe there was one last, hidden level—Code Black. So far since the chart’s inception there had only been cause for a Code Orange and not a single incident requiring a Code Black. Such an imminent threat was why they had The Cause to begin with.

“Do you think they have anything to do with the Calloways, sir?” Scissors asked, checking the pages on his notebook.

“Highly unlikely, but we can’t take any chances.”

The Calloways were the Row’s mysterious, unknown benefactors who had serendipitously stepped in to support the Row after the city withdrew its funding. Little was known of them—who they were, where they came from, or why they sent the money in the first place. But like clockwork, at the first of every month, an unmarked envelope with a check for $1500 arrived incognito at the doorsteps of the Row, delivered by a tall man in a black suit and dark sunglasses, who drove an equally black car with tinted windows.

Every time T.W. heard the Calloways’ name, he would immediately take a cigarette out and twirl it between his fingers until it shredded, leaving trails of tobacco behind him as he paced the floor. Seeing this, the other orphans feared the Calloways were some kind of a threat.

“I want you to check up on Muscles and make sure everything is going smoothly. Also if you see Matches, make sure to tell him to lay off the gasoline this time around. We can’t chance him lighting himself or someone else on fire or burning down the orphanage.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And, Scissors, one last thing.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Close the door behind you. I don’t wish to be disturbed. I’ll be in the mess hall momentarily. You can start without me.”

“Sir?”

“It’s nothing. I just need a moment to myself.”

With a confused look, Scissors left the office, closing the door behind him, leaving T.W. to his solitude. T.W. took one last drag from the cigarette before depositing it in an ashtray on his desk. He got up and moved to the window, his favorite place to ponder. The outside was dreary and cloudy with the chance of rain ominous on the horizon. The street below, like most of the surroundings, was empty save for the weeds.

The neighborhood, like much of Detroit, lay in waste and abandonment, hardly the proper place for an orphanage. Douglas Street was so rundown and decrepit that even hope couldn’t flourish there. was lined with more potholes than pavement and the sidewalks were home to a whole bunch of garbage—crumbled newspapers, scattered debris, abandoned cars, empty shopping carts—and one vagrant, Stinky Pete, who spent his days pushing a shopping cart full of discarded things.

T.W. watched as Stinky Pete picked up a bottle from the ground and raised it to his mouth for a moment, shook it, and then vehemently threw it down. Looking up, he waved to T.W. with a dirty, grease-covered hand. T.W. returned the gesture and then continued his vigil of the dirty, deserted street below.

He spotted Big Mama, a heavyset black woman and the Row’s loveable caretaker and Head Supervisor, sitting on a bench, taking a break from her cleaning, and working on her favorite pastime, stitching a new shirt for one of the orphans. Her warm smile radiated optimism, being the only upbeat sign of life for miles around. “Oh, Lordy,” T.W. heard her call in between stitches, “Desolation Row sure is looking good today, Lordy, yes.”

From his vantage point, T.W. begged to differ.

Surrounded by abandonment, the Row was constructed in a part of Detroit not only deserted by its people, industry, and businesses but by the city itself, which had forgotten to send the Row’s monthly stipend for the past year. Wedged between an abandoned pawnshop and a derelict textile plant, it was one of the few still standing and functional buildings on the block. Its red-bricked walls appeared like a fire veiled by billows of dreary, hazy smoke.

Thanks to looters, the windows of the abandoned pawnshop had been busted and boarded over, while the door was a gaping hole. The inside was stripped of anything of worth, including the copper wiring, most likely sold as scrap. All that remained of its glory days was a faded sign, reading “Open for Business.” No one had bothered to turn it to “Closed.”

The metal roof of the textile plant had rusted to a dull orange, while the brick walls were of such a dark gray they never hinted at a sunny day. During the late seventies the back half of the building caught fire and despite the Fire Department (the Row’s third incarnation after the School and Library closed) being right next door, no fire trucks or firemen came to quench the flames. Seeing the calamity as an opportunity for cheap urban renewal, the city decided it was best for the building to burn to the ground.

Mother Nature clearly disagreed. She released such a massive rainstorm that the fire was doused in less than an hour, saving not only the abandoned textile plant, but most of Douglas Street as well. What remained were partially burned buildings, half piles of ashes and half in a state of ruin.

A massive Ford automobile plant, made vacant due to greener pastures overseas, stood across the street more like a metallic castle than a factory. Seemingly endless, it dominated the landscape, sprawling for almost an entire mile, a vast industrial emptiness, collecting debris, cobwebs, and rodents.

The only thing still open for business and within walking distance of the Row was the Detroit House of Corrections—also known as the state penitentiary or pen for short. It was not only the biggest prison in the state of Michigan, but the entire Midwest, crammed full with murderers, thieves, arsonists, substance abusers, dealers, and the pits of society, or rather the forgotten masses of Detroit. In a lot of ways, prisoners were really just grown-up orphans abandoned by society. They, like the orphans, were always there, scars pushed out of sight and concealed in darkness—the blind eye of humanity.

Despite their close proximity, neither one would have been readily aware of the other if it had not been for a technicality that resulted in large monthly shipments of supplies, originally destined for the prison, being dropped off on the doorsteps of the Row instead. The prison’s address—3959 Douglas Street—was often confused with the Row’s address—2959 Douglas Street. As a result, the Row often received large packages of canned goods, reading materials, bed sheets, soap, cartons of cigarettes, and stacks of letters addressed to such notorious criminals as Sonny “One-Tooth” Sullivan, Harry “Menace” MacArthur, Mickey “No Dice” Paulson, Terry the Terrorizer, “Crazy-eye” Hopkins, and Juan “AK-47” Martinez. There were even a few addressed to the Detroit Streaker, who despite rumors of capture was still at large.

Compared to the rest of the neighborhood, the Row itself was in quite good condition. Originating from the early days of Detroit, long before its decline, it was constructed by one of the city’s leading architects, a man so renowned that he was lost in the back pages of Detroit’s history books and never heard from since. This unknown architect came from a time when things were built to last. The Row stood as one of his most crowning and enduring achievements, though no one bothered to notice, save for the orphans of Desolation Row.

T.W. stood erect in front of the Row’s third floor window, with his right arm behind him like a general surveying the battlefield before the cannons fired, pondering the beauty hidden underneath so much wasted potential and relishing the silence surrounding him. Such a moment was a luxury seldom found in an orphanage of thirty plus orphans. As the oldest, it was his duty to look after each and every one of them. He did not think of his responsibilities as a burden or an inconvenience but rather a calling.

As he gazed off into the distance, a large flock of seagulls—also known as dumpster chickens—made their way from the dump behind the Row towards the abandoned automobile plant. T.W. pulled a watch from his jacket, looked at the time, and smiled. As always, the dumpster chickens were on schedule.

Watching them in flight always made him wonder what it would be like to fly like a bird. To have wings, to soar, to have everything below him looking up. Perhaps there was no greater sense of freedom. But, like freedom, everything came with a price, as Icarus learned when he flew too close to the sun and plummeted. The fall was something all orphans eventually faced. T.W. just hoped to have his wings long before that day came.

T.W. turned away from the window and stared down at his typewriter. He debated whether or not to attempt writing. His novel wasn’t going to write itself. So far he was stuck on page 364, awaiting a major plot point to materialize. The story just wasn’t speaking to him anymore. He had the characters, but not the climax, the middle and beginning but no end in sight. The way things were going, he’d be an orphan without an orphanage if he didn’t find a solution.

What would Hemingway do, old boy?

“I learned never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it,” he thought, drawing inspiration from his mentor Hemingway.

He had tried to always follow that advice, but this time the well had gone dry.

The ringing of the lunch bell, signaling noon, broke his reverie. He released a deep breath, straightened his jacket, and stepped away from the window, deciding to save his writing for another day. He opened the door to his office and was somewhat surprised to discover he was not alone.

“Good God, Ray Charles, what in the Hemingway are you doing here? I thought I told you to get your binoculars cleaned and find Seafood.”

“Sorry, sir,” Ray Charles said, adjusting the knobs on the binoculars in an attempt to bring T.W. into focus. When it came to sight, Ray Charles was as blind as a mole and couldn’t see more than a few feet in front of him. Lacking proper medical assistance at the Row to fix his nearsightedness, T.W. recruited his first lieutenant—there was no second—The Wiz, age eleven, to formulate a remedy.

The Wiz was the smartest orphan at the Row, with a perfect IQ of 200 and a photographic memory. He had long wild hair that clung to his head like a pile of dirty laundry. Glasses the size of two magnifying lenses sat on his small nose, making the rest of his face appear tiny. Like a mad scientist, he always wore a white apron. Its pockets full of beakers, test tubes, half-chewed pencils, and the occasional rat with its tail dangling out like a piece of string. A calculator was never far from his hand, and throughout the day he was seen punching random calculations, formulating outcomes, and figuring mathematical probabilities. He was the orphan most likely to develop a teleportation machine capable of time travel.

Within a few days, The Wiz had modified a pair of binoculars, attached a strap to them, placed them on Ray Charles’s head, and then adjusted them to meet Ray Charles’s ocular needs. After a quick punching of numbers on his calculator, The Wiz calculated that Ray Charles had a 74.87—repeating of course—percent chance of seeing what was in front of him.

“Can you see anything, Ray Charles?”

“No, not yet.”

The Wiz turned a dial.

“How about now?”

“Sure can.”

“How’s it feel?”

“A little jacked up.”

“You’ll just have to get used to it, Ray Charles.”

When The Wiz was finished, Ray Charles had the long-distance vision of an eagle, but had to constantly adjust the dials to see things up close. As a result his vision was always in and out of focus, equal parts nearsighted and farsighted.

Ray Charles was still working the dials as T.W. stood outside his office door, losing patience while waiting for a reply. “Ray Charles? What are you doing here? Shouldn’t you be in the rec room with the rest of the men?”

“Yes, I know sir, but . . . you see . . . I was wondering . . .”

Ray Charles paused and removed the binoculars from his face, revealing two rheumy eyes, dripping water like a leaky faucet. Overcome with emotion, he was unable to speak.

“Come with me into the office.” T.W. motioned, looking distraught. Ray Charles followed him and closed the door.

“Well, what is it?”

“Sir, I was just thinking that, well . . . I could volunteer myself—for The Cause—and, you know, let myself be adopted.”

It was not that Ray Charles really wanted to be adopted, but rather that he was willing to do almost anything—including taking a bullet if it came to it—for his best friend and mentor.

“Good God, man, don’t be ridiculous. I wouldn’t let one of those incompetent nincompoops take away one of my own. We have to stick together. It’s a mad, crazy world out there. It’ll tear an orphan apart. Remember what happened to Snuggles?”

Ray Charles gulped. “Right, sir. What was I thinking? Of course I don’t want to be adopted.”

“Good, now remember the first thing in any—” Before he could finish, Scissors came barging into the room.

“Sir, we have a situation.”

“What now?”

“They’re here. The Charlies. They’re early, sir.”

“Good God, man, put a pickle on some bread and call it a sandwich.”

“What should we do?”

“Sound the alarm!”

“Roger that.” Scissors left the room like a bolt of lightning.

“We’ll discuss this in more detail later, Ray Charles. For now, just remember your duties and look sharp.”

“Yes, sir.” Ray Charles said, a little too forlorn for T.W.

“Can I count on you soldier?”

“Sir, yes, sir.” Ray Charles said it like he had a pair.

“Alright then, help Scissors round up the troops and make sure they take up their positions. We haven’t a moment to lose.”